Your Index Fund Is Now a $10 Trillion AI Bet—And 95% of Companies See Zero Returns

Seven companies control one-third of the S&P 500 while spending $400 billion annually on infrastructure that enterprises can't monetize. What breaks first when the circular dependency snaps.

Your index fund isn’t what you think it is anymore.

What you believe is broad exposure to the U.S. economy is, in practice, a concentrated bet on seven companies pulling off a near-flawless AI monetization story.

The Magnificent Seven now make up roughly one-third of the S&P 500. About 32% as of mid-November 2025. Nvidia alone is about 8% of the entire index. More than twice the weight of the entire energy sector.

So the “diversified” fund in your retirement account has quietly turned into something else. A wager that these companies can do three hard things at the same time. Monetize AI fast enough to justify the spend. Build physical infrastructure fast enough to run the models. Avoid major geopolitical disruption while the supply chain remains fragile.

This concentration happened gradually, then suddenly. Most people holding standard index funds don’t realize they’ve been repositioned without their consent.

I spent the past month pulling apart every piece of verifiable data I could get my hands on around the “AI bubble” question. Institutional surveys. Academic studies. Corporate filings. Hedge fund positioning. Thousands of Reddit threads. X posts. LinkedIn debates. YouTube analysis from people who clearly do the work and people who clearly don’t.

What came out of that isn’t a clean bubble versus no-bubble answer. It’s more uncomfortable.

It looks like two markets operating at the same time. One rational. One manic. Both sitting on a foundation that can crack without warning.

The question isn’t whether to have AI exposure. If you own an index fund, you already have it. Probably more than you intended.

The question is what happens next, and whether the numbers actually support what’s priced in.

The Case Against a Bubble: Why This Isn’t 2000

The comparison everyone reaches for is the dot-com crash.

It’s the nearest scar tissue. It’s also a lazy analogy if you look at the math.

At the March 2000 peak, Cisco Systems, the infrastructure king of the internet buildout, traded at well over 100 times forward earnings. Around 130 times by some estimates. Over 200 times trailing.

Nvidia today, playing the same role in the AI buildout, trades at about 30 times next-twelve-month forward earnings and roughly 54 times trailing earnings.

Those aren’t the same universe.

The top four tech leaders in 2000, Microsoft, Cisco, Intel, Oracle, averaged a two-year forward price-to-earnings ratio around 70 times. Today’s hyperscalers, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, average in the high-20s. Roughly 29 to 30 times forward earnings.

The Nasdaq-100 hit a forward P/E around 60 times in March 2000. In late 2024 and 2025, it traded in the mid-20s. About 26 to 28 times.

So yes, today’s leaders are expensive. But they’re measurably two to three times cheaper than the dot-com leaders were at a similar moment in the buildout.

If you adjust for growth using the PEG ratio, the contrast gets even cleaner. Cisco’s 2000 PEG was well above 7. Nvidia’s current PEG is roughly 0.8 to 1.0. Investors are paying a fraction of the premium per unit of growth.

And the other thing people forget is profitability.

In 2000, only a small minority of dot-com companies were profitable. Today’s AI leaders throw off real free cash flow. They buy back stock. Some pay dividends. Goldman Sachs has described the current rally as “driven by fundamental growth rather than irrational speculation about future growth.”

Even Nvidia’s growth is not a storytelling artifact. Its revenue surged 126% in its latest fiscal year, covering most of calendar 2023, from $27.0 billion to $60.9 billion. That’s not “potential.” That’s realized demand.

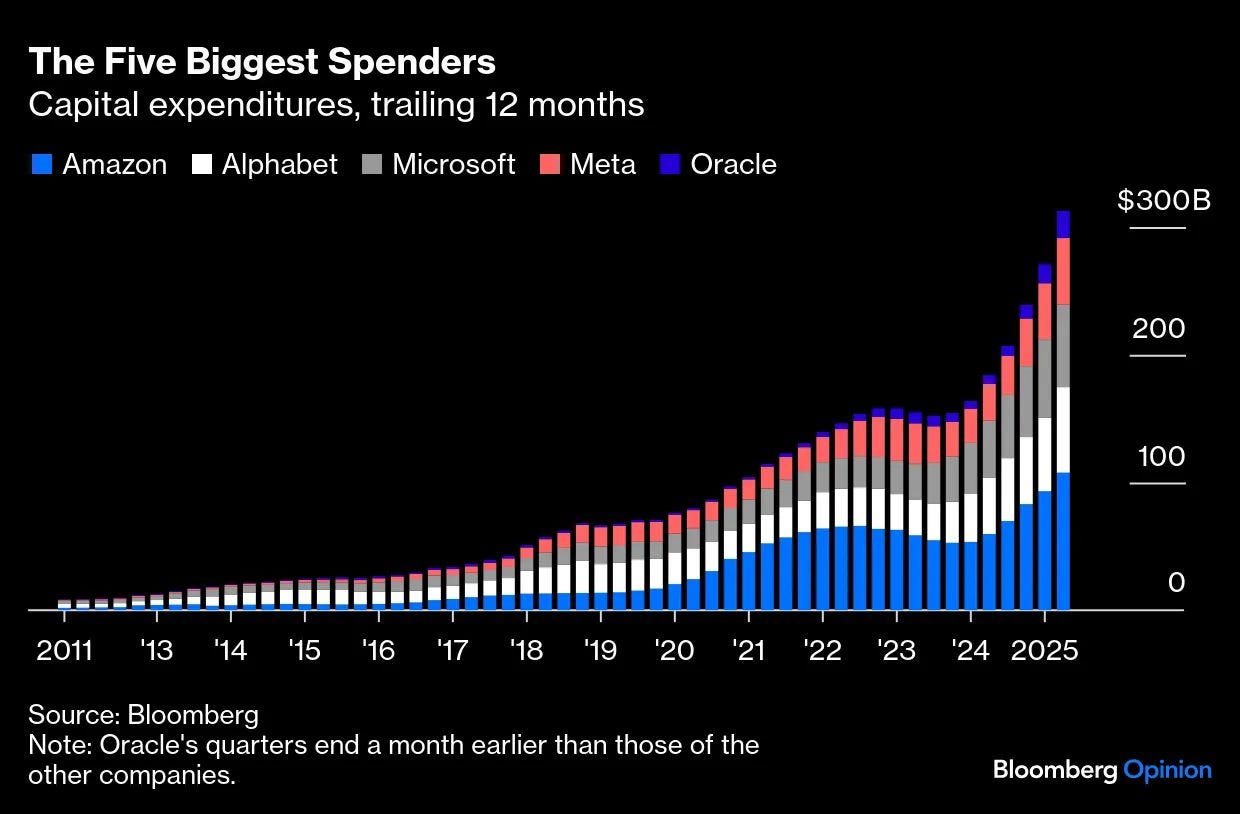

Then there’s the infrastructure spend. It is real. It is visible. It is happening in cash terms.

Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, and Alphabet have raised their 2025 capex guidance substantially. Alphabet to about $91 to $93 billion. Amazon to roughly $125 billion. Meta to $70 to $72 billion. Microsoft doesn’t give a single annual number, but the trajectory is clearly in the same neighborhood.

The bottleneck is supply, not demand. Nvidia is selling through inventory in months. That’s a very different setup than the dot-com era’s “build it and they will come” financing.

A true financial bubble also has a psychological signature. Euphoric, all-in crowd behavior.

That’s not what the sentiment data shows right now.

The American Association of Individual Investors Sentiment Survey for mid-November 2025 shows bearish sentiment at 49.1%, unusually high, while bullish sentiment sits at 31.6%, below the historical average of 37.5%. At the dot-com peak in March 2000, bullish sentiment reached 75% with bearish sentiment below 20%.

Today’s vibe is closer to paranoia than champagne.

Institutional positioning looks two-sided too. Thirteen-F filings show real disagreement among serious players. Stanley Druckenmiller’s fund exited its Nvidia position entirely by mid-2025. Renaissance Technologies was a large net buyer of Nvidia in 2025, with Nvidia becoming one of its top holdings. That’s active price discovery, not a herd.

Even on Reddit, the tone is more risk-aware than people give it credit for. One highly upvoted thread on r/investing said: “impossible to time... but what if we still have 2-3 years before popping?” That’s speculation, but it’s not 1999 naïveté where people quit jobs to day-trade profitless companies because they added “dot-com” to the name.

So if you stop here, the bull case is genuinely strong. Reasonable multiples relative to 2000. Massive profitability. Real demand for infrastructure. And a surprising lack of euphoria.

Selling everything because “it feels like 2000” would be a behavioral mistake built on a false comparison.

But stopping here misses what I think is the more important split.

The Private Market Bubble

Public markets look broadly rational.

Private venture capital does not.

As of Q3 2025, AI deals account for about 63% of trailing 12-month U.S. venture capital dollars. That’s an absurd concentration.

For comparison, at their 2022 peaks, fintech captured about 17% of VC dollars and crypto roughly 7% during their respective booms. The AI VC boom is an order of magnitude larger and more concentrated than any recent hype cycle.

PitchBook estimates that in 2025, about 41% of all U.S. VC funding has gone to just 10 startups. Eight of them in AI. In 2025 alone, OpenAI, xAI, and Anthropic have together raised on the order of $50 to $60 billion plus, depending on how you count overlapping rounds and commitments.

Goldman Sachs analysts, even while constructive on public AI, have said they are “worried about the large gap between public and higher private market valuations.”

And venture investors themselves sound like people who know the room is overheating. Rebecca Kaden at Union Square Ventures called it a “funky time” to be investing.

This is where the 2000-style behavior lives. Hope-and-hype financing. Capital chasing theme dominance. Valuations that aren’t anchored to near-term economics.

The question I can’t resolve cleanly is whether a private-market deflation pulls down public markets with it, or whether it mostly stays contained and simply resets startup valuations while public incumbents keep compounding.

I can see both paths.

But pretending the private bubble doesn’t matter is also wrong. These markets are connected through talent, supply chains, customer budgets, and narrative.

When the private market air comes out, it will change behavior across the ecosystem. Hiring slows. Spend gets scrutinized. Growth-at-any-cost stops being cute.

That shift tends to hit the marginal players first. Then it starts leaning on the leaders.

The $400 Billion Question: Where’s the Return?

The more sophisticated risk here isn’t “are valuations high.”

It’s the circular dependency sitting at the center of the entire AI trade.

I think of it as a three-link chain. And each link depends on the next.

First, Nvidia’s valuation, and the sell-side narrative of hundreds of billions per year of AI infrastructure capex, depends on hyperscaler spending commitments.

Second, hyperscaler valuations depend on enterprise AI revenue growth to justify that capex.

Third, enterprise AI spending depends on measurable return on investment from AI implementations.

Break one link and the chain doesn’t “adjust.” It snaps.

That’s not theoretical. You can see it in the data.

A 2025 MIT study found that U.S. enterprises invested roughly $35 to $40 billion in internal AI projects, yet about 95% of those efforts produced no measurable ROI within the 12 to 18 month measurement window. The researchers noted this could reflect implementation lag rather than technology failure, but the lack of near-term returns is measurable and widespread.

S&P Global’s enterprise survey flagged “mixed outcomes” and noted “project failure rates appearing elevated.”

BCG finds that only about half of companies hit their cost-reduction targets from AI projects, and roughly 60% fail to achieve material value at all. The top 5% of “future-built” firms, by contrast, see five times the revenue uplift and three times the cost reductions of average adopters.

So you have a very clear tension.

The enterprise ROI isn’t showing up broadly yet.

At the same time, AI talk is everywhere. FactSet data show that in Q2 2025, about 57% of S&P 500 companies mentioned “AI” on earnings calls. The SEC is actively warning companies about “AI-washing” and generic risk disclosures. That behavior rhymes with 1999’s dot-com name-change era, even if the underlying tech is real.

Now place that alongside hyperscaler spending.

In Q3 2025 alone, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, and Meta together spent about $113 to $114 billion on capex. And by Q3 2025, guidance moved up meaningfully. Alphabet to about $91 to $93 billion for 2025. Amazon to roughly $125 billion. Meta to $70 to $72 billion. Microsoft again doesn’t give a single annual figure, but the direction is clear.

On current guidance, major U.S. hyperscalers are tracking toward several hundred billion dollars per year. Approaching $400 billion annually. And multiple sell-side houses project cumulative AI and data-center capex exceeding $1 trillion by the late 2020s.

This is not normal corporate spending. This is a national infrastructure project funded by a handful of balance sheets.

And it’s starting to show up in free cash flow.

An October 2025 Morgan Stanley report warned that hyperscaler free cash flow growth has turned negative and could shrink by around 16% over the next twelve months. A 2024 JPMorgan analysis modeled scenarios where some hyperscalers’ free cash flow margins go negative under aggressive AI capex plans.

This is the uncomfortable part.

The capex is being funded by mature businesses like search and digital advertising. Businesses that are profitable, but not exactly in hypergrowth mode. Meanwhile the AI revenue needed to justify the spend hasn’t shown up at scale in enterprise ROI data yet.

So hyperscalers are effectively betting their legacy cash engines on a future productivity boom that 95% of enterprises aren’t measuring.

That setup can work. It can also break fast.

If enterprise customers don’t see returns, they slow AI transformation spend. Hyperscalers miss AI revenue targets. With free cash flow already strained, they protect margins by slowing 2026 and 2027 capex. The moment a CEO signals that, the multi-hundred-billion-dollar order book looks like it evaporated overnight.

The primary risk isn’t a valuation collapse by itself.

It’s the fragility of the order book that makes the valuation feel “obvious.”

The Energy Wall: A Physical Constraint Nobody Wants to Talk About

Beyond the financial chain, there’s a physical one that doesn’t care what the Fed does.

U.S. Department of Energy data show that data centers consumed 4.4% of all U.S. electricity in 2023, projected to reach 6.7% to 12% by 2028.

The International Energy Agency projects global data-center electricity demand will at least double from roughly 460 terawatt-hours in 2022 to over 1,000 terawatt-hours by the mid-2020s, with further growth through 2030. In the U.S., data centers are projected to account for half of all electricity demand growth by 2030.

The grid doesn’t expand on a quarterly cadence.

In key U.S. data-center hubs like Northern Virginia, interconnection waits can stretch to seven years or more. In other high-growth markets such as Texas and Ohio, surveys report multi-year delays, with some projects facing similarly extreme timelines.

The IEA estimates that a meaningful portion of planned global data-center capacity is at risk of delay or cancellation due to grid limits.

Ireland is the cautionary tale here. Data centers already consume over 20% of the country’s electricity. About one-fifth of total demand.

This isn’t a “sentiment risk.” It’s a watts risk.

Hyperscalers can want to spend. They can have the money. They can have the chips on order.

If they can’t get power connected, projects slip.

And if projects slip, the capex plans have to be revised. Not because management lost faith. Because the physical input isn’t available.

Everyone wants to price AI as infinite scale. The grid is telling a different story.

The Taiwan Single Point of Failure

Then there’s the risk everyone knows is there and nobody wants to talk about for too long.

TSMC produces over 90% of the world’s most advanced logic chips at the leading-edge process nodes.

Bloomberg Economics estimates that a full-scale war over Taiwan could cost the global economy around $10 trillion. A separate analysis by the Institute for Economics & Peace estimates the cost of a prolonged blockade at about $2.7 trillion. Roughly 40 times the estimated economic impact of the war in Ukraine.

The Taiwan Strait is one of the world’s major shipping chokepoints, carrying a substantial share of global container traffic.

A conflict scenario halts chip exports. The market response is not subtle. You’d expect an instantaneous collapse in tech-heavy indices. Flight-to-safety moves. Oil, Treasuries, gold spiking on supply shock and panic.

I’m not assigning certainty here. I’m saying the structure of the market makes the consequences severe because concentration is severe.

Low probability. Total impact.

That’s tail risk. And tail risk is what destroys over-concentrated portfolios.

What the Data Suggests

After pulling all of this apart, I’m left with a split-screen picture.

Public equities show something close to rational pricing, backed by real profits and genuine technological progress.

Private markets show classic bubble behavior, with valuations that feel detached from fundamentals.

Both worlds rest on a several-hundred-billion-dollar annual capex cycle that assumes productivity and revenue arrive soon enough to justify it. And the enterprise ROI data says that, for most companies, that payoff still isn’t showing up inside the measurement window.

That’s the tension.

Now, I do want to be careful here. I can’t “prove” which path wins in advance. The best I can do is lay out scenarios that map cleanly to the data.

The base case, and I’ll call it roughly 60%, is that the AI revolution is real and the infrastructure buildout is necessary. The 95% of firms seeing zero ROI reflects lag and organizational friction, not technology failure. Free cash flow strain is a temporary investment cycle. Productivity gains arrive, revenue catches up, and the buildout runs for five to ten years with periodic corrections.

The alternative case, roughly 25%, is that the buildout hits the power wall before enterprise ROI arrives broadly enough to justify the spend. Projects get delayed for power reasons. Hyperscalers are forced to push out or trim 2026 and 2027 capex. AI equities correct 30% to 40% over six to nine months as the order book narrative breaks. The tech keeps improving, but the timeline extends and valuations reset.

The tail case, maybe 15%, is geopolitical shock. Taiwan-related disruption, chip supply chain breakdown, and a violent repricing. That’s the low-probability, high-impact scenario.

So the data doesn’t support the easy conclusion of “sell everything, it’s a bubble.”

It also doesn’t support sleepwalking through concentration risk, circular capex dependency, enterprise ROI shortfalls, grid limits, and the Taiwan single point of failure.

Where I See the Opportunities and Risks

The concentration in the Magnificent Seven is both the opportunity and the vulnerability.

These companies are genuinely changing how value is created in the global economy. But they’ve also grown into such a large portion of the index that “they’ll do fine” is no longer a comforting thought. Their success is already priced as the default.

What I’m watching most closely is hyperscaler capex language. Not the numbers alone, the language. If Microsoft, Google, Amazon, or Meta signals any meaningful reduction in 2026 or 2027 spending plans, that’s your trigger for the capex disappointment path.

The free cash flow strain flagged by Morgan Stanley and modeled by JPMorgan suggests they are closer to that inflection point than most investors want to admit.

The power constraint is still underpriced. The Department of Energy and IEA projections point to fast demand growth. The interconnection queues point to slow supply response. That mismatch is a ceiling on how fast this can build, regardless of how much money is available.

Markets love growth stories. Power lines move on permitting timelines.

The private-market valuation gap worries me more than public multiples. When 63% of VC dollars flow into a single theme, and Goldman is openly saying private valuations look high relative to public markets, that’s the kind of setup that tends to end with a reset.

The private bubble deflates first. The open question is whether it creates contagion or creates opportunity.

And on hedging, I’m not going to pretend there’s a clever trick. The real-world hedges for the risks above tend to be boring. Power infrastructure benefits if electricity limits become the binding factor. Gold and commodities tend to help in geopolitical stress and supply shock.

None of that is a bet against AI. It’s a recognition that the risks here are not “software disappoints.” The risks are physical and geopolitical and balance-sheet related.

Liquidity matters more than usual too. If you want the ability to buy quality AI names 30% to 40% lower in the power-delay scenario, you need capital that isn’t already trapped in the same crowded trade.

The behavioral problem is that dry powder feels stupid when everything is going up. That’s exactly why it works when it’s needed.

I’m not giving allocation advice here. But structurally, if you accept the setup described in this investigation, you want exposure that can compound in the base case without being wiped out in the tail case.

What to Watch

The Q4 2025 and Q1 2026 earnings calls matter more than usual. Any reduction in 2026 or 2027 capex guidance shifts weight toward the alternative scenario. If companies cite grid connection delays or power availability, that’s hard evidence the ceiling is physical, not financial.

I’m also watching whether the enterprise ROI picture improves. If the MIT-style “95% no measurable ROI” story starts dropping toward 80% or 75% over the next couple quarters, it suggests the productivity gains are finally arriving inside the measurement window.

PitchBook’s VC concentration is another tell. If AI’s share of VC dollars keeps pushing toward 70%, the private bubble is still inflating, which usually means the eventual deflation is uglier.

And on power, the signal I care about isn’t a forecast. It’s project-level evidence. Specific reports of hyperscaler data center builds getting delayed for power reasons.

On geopolitics, it’s ongoing monitoring. Rhetoric changes. Exercises change. Sanctions change. The probability distribution shifts. The consequence stays the same.

The Bottom Line

There’s a genuine technological revolution happening. There’s also a bubble sitting on top of parts of it, especially in private markets.

Valuations will correct at some point. The timing is unknowable. The technology will keep improving regardless. Winners will be spectacular. Losers will be catastrophic.

What’s different this time is that concentration has quietly turned “owning the market” into “owning seven companies.” Whether you intended that or not.

The risks are not abstract. They’re measurable. Circular capex dependency. Enterprise ROI shortfalls. Hyperscaler free cash flow strain. Grid limits. Taiwan as a single point of failure.

The opportunities are also real. Productivity gains that compound. Infrastructure buildout that creates durable value. Public-market leaders that are profitable in a way 2000 leaders weren’t.

The data doesn’t support a binary decision. It supports understanding that your index exposure is an AI bet, knowing what breaks that bet, and structuring so you can survive both the base case and the ugly ones.

The goal isn’t to predict which scenario arrives when.

It’s to still be standing when it does.

This article comes at the perfect time and your deep dive into the concentration of index funds in the Magnificent Seven for AI is incredibly insightful, though it also makes me wonder if this isn't simply the unavoidable outcome when only a few players can truly operationalize and scale something as complex as cutting-edge AI infrastructur.

Regarding the topic of the article, this piece realy builds effectively on your earlier work regarding market concentration. Your analysis of AI's disproportionate impact on index funds is incredibly insightful. The description of two simultaneous markets is brilliant; it makes one pause.