The Real AI Trade: Contracts, Kilowatts, and the Constraint Nobody's Pricing

Data centers want power in 24 months. The grid delivers in 7 years. That gap is the trade.

In 2016, Nvidia traded around 30 times earnings and most serious money treated it like a premium gaming company with an odd side project in scientific computing. The AI training demand story existed. It just didn’t feel like an underwriting fact yet.

Seven years later, the bears weren’t “a little early.” They were structurally wrong. They underwrote the category. Nvidia underwrote the binding constraint.

I’ve been looking for the next version of that setup. Not another chip company. Not another model vendor. Something lower in the stack, where physics sets the pace.

And when I traced where the electricity is supposed to come from for all these announced data center builds, the story got uncomfortable fast.

The new bottleneck is power.

One disclosure before I go further. I worked from filings, earnings calls, press releases, and regulatory documents. I treat the numbers as directional and focus on what contracts, backlogs, and timelines imply.

The Constraint-First Framing

Most people hunt for the “next Nvidia” by scanning the same surface area. New models. New chips. New software platforms. That’s the obvious category.

I think the better approach is constraint-first.

What is the one enabling input the entire stack can’t grow without?

In phase one, that input was training compute. In phase two, it’s electricity and delivery timelines. Not vibes. Timelines.

If AI is the story of bits, this part is the story of atoms.

Here’s the causal engine I can’t unsee.

Data centers want power on a consumer-tech schedule. The power system delivers on an industrial and regulatory schedule. That mismatch creates scarcity. Scarcity creates pricing power. Pricing power rewrites who captures value in the stack.

I don’t need a grand theory to say that. I just need the timelines.

Data centers want power in 18 to 36 months.

Gas plants take 2 to 3 years from decision to commissioning.

Wind and solar take 5 to 10 years when permitting is real.

Nuclear takes 7 to 15 years.

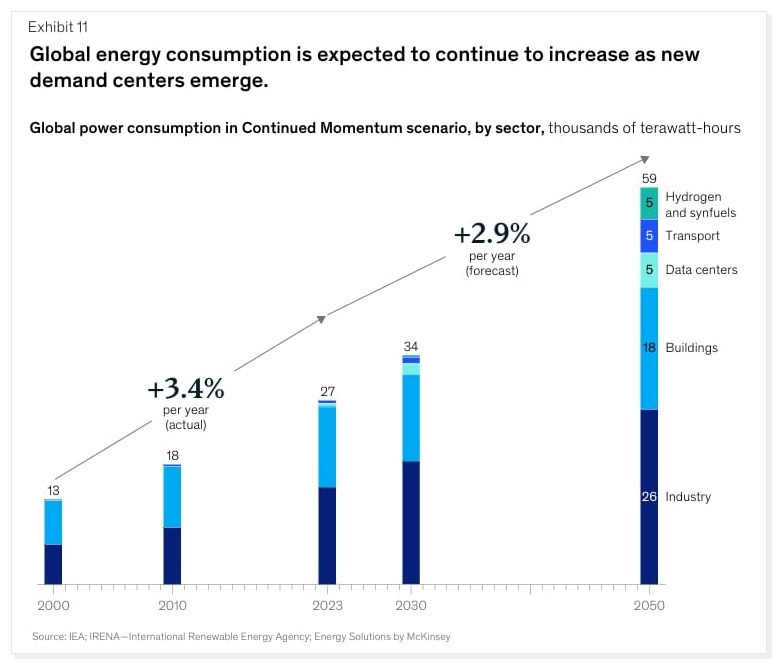

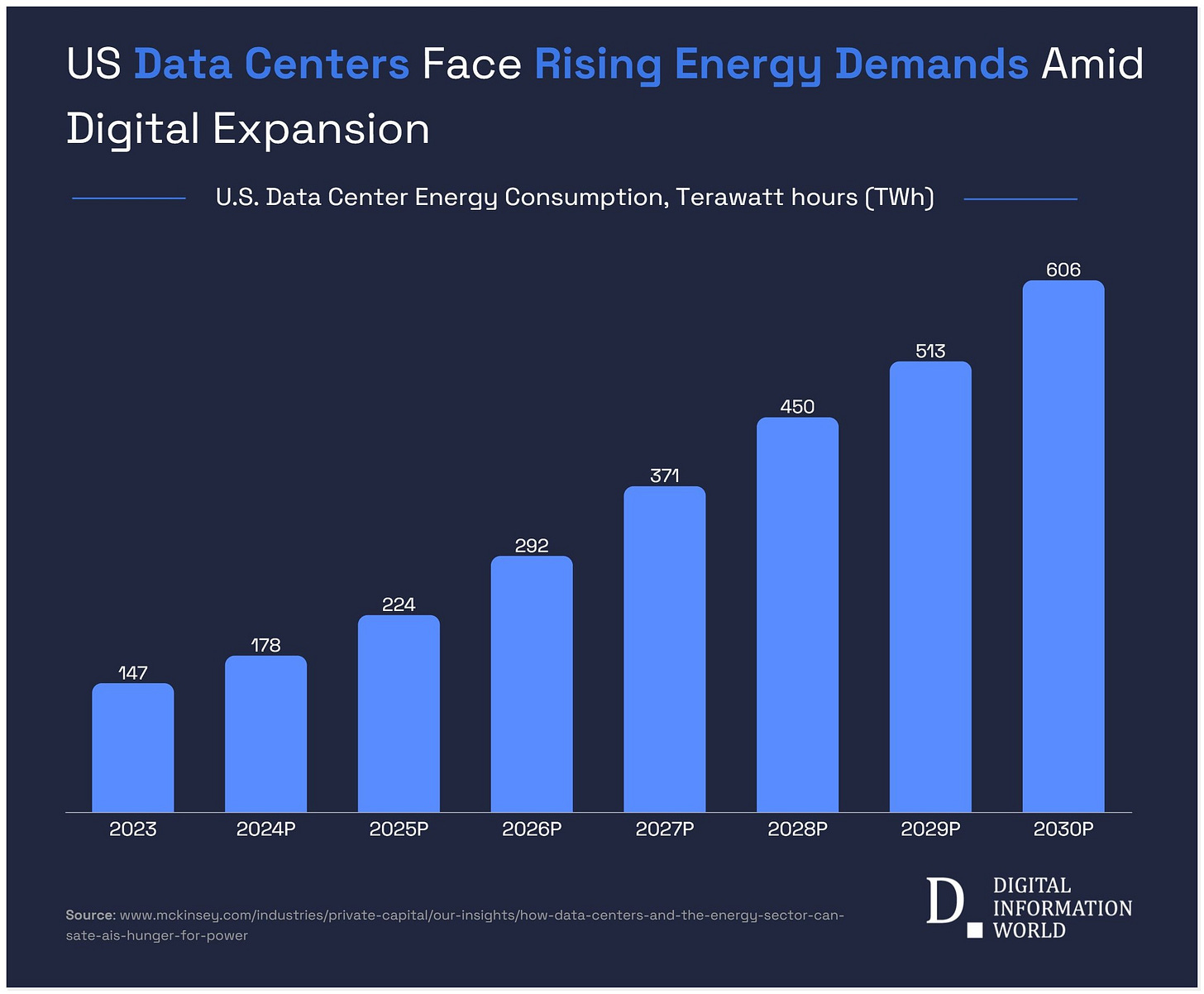

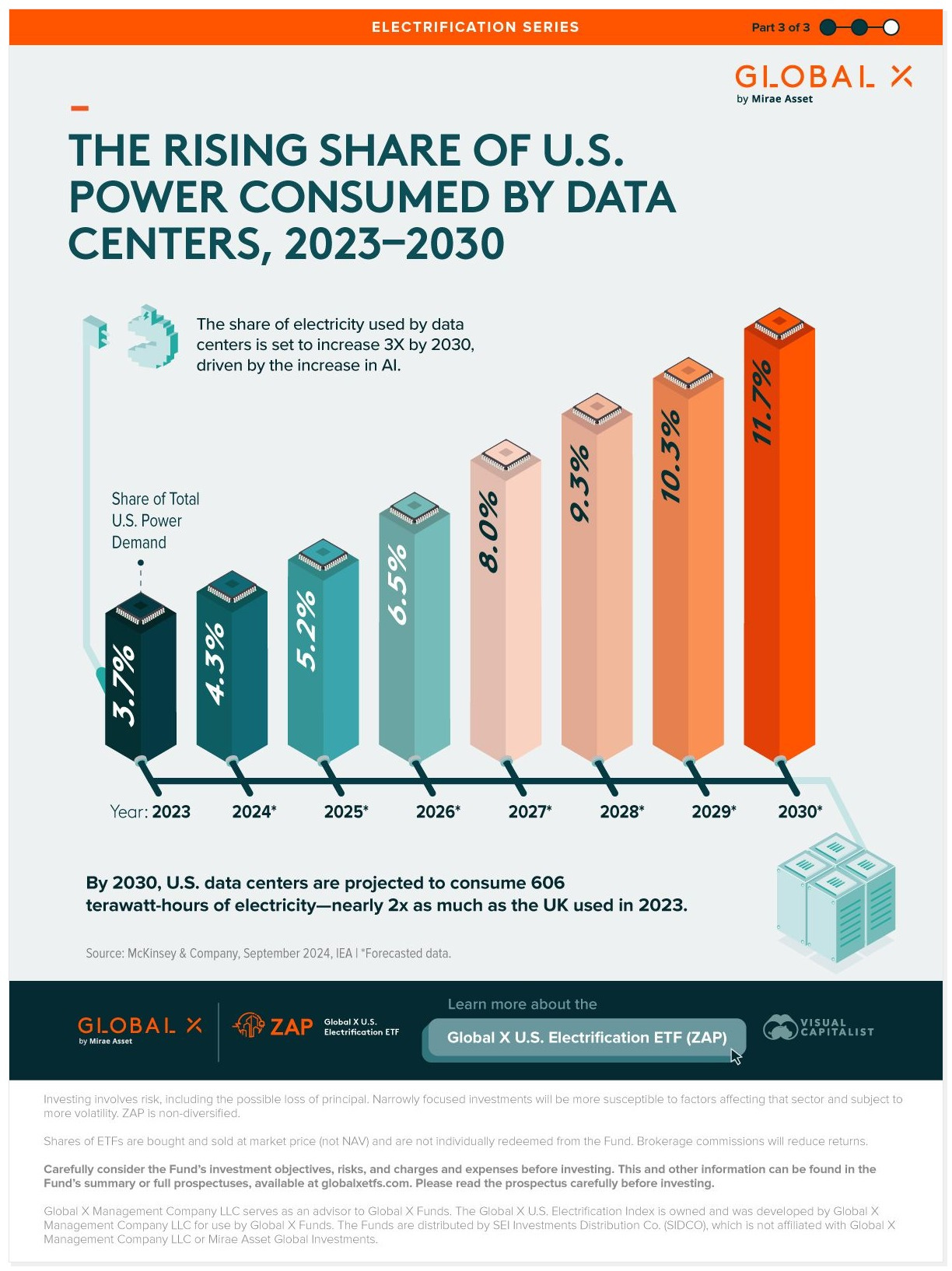

Data center electricity demand is forecast to grow 165 percent by 2030.

The point isn’t whether the forecast is off by a few points. The point is that the grid can’t move on software timelines.

So what becomes valuable in a world like that?

Time-to-power.

Utilities aren’t Nvidia. If the thesis requires you to believe utilities will suddenly have Nvidia-style margins, it’s not a thesis. It’s a daydream.

The comparison is structural, not financial.

Nvidia’s 2016 setup was a physical bottleneck plus a category error. Demand was growing faster than supply could be built. The market kept thinking “gaming hardware.” Meanwhile, the world was quietly reorganizing around the fact that a small number of companies could deliver the scarce input.

That’s the parallel I care about.

Today’s setup is a physical bottleneck plus a category error. The market still thinks “bond proxy.” Meanwhile, hyperscalers are acting like power is a scarce operating right that needs to be locked up.

The analogy breaks on margin profile. It holds on bottleneck logic.

Category Error

A lot of capital buys “AI exposure” by label. Technology bucket. Semiconductor bucket. Software bucket.

But economic exposure doesn’t care what bucket your index provider uses.

If a company’s cash flows are increasingly hyperscaler-driven, and its growth is increasingly determined by data center build schedules, it’s functionally part of the AI stack even if it’s classified as a utility or an industrial.

So why does the market keep pricing large parts of the enabling layer like bond proxies?

Mandates. Labels. Habit.

It’s easier to buy the story than to buy the constraint.

That’s not a moral failing. It’s just how institutional plumbing works. And plumbing is where mispricings hide.

Press releases are cheap. Contracts are not.

Targets are marketing. Contracts are behavior.

When I want to know what’s real, I don’t start with “capacity plans.” I start with signed commitments, duration, counterparties, and commissioning windows.

Three tells matter. Duration, scale, and commissioning windows.

Here’s what I found when I stopped reading targets and started reading commitments.

In May 2024, Brookfield Renewable announced a 10.5 gigawatt renewable power agreement with Microsoft, with a term listed as 2026 to 2035. The announcement described it as the largest corporate power purchase agreement ever signed and gave a revenue range of $3 to $5 billion over the contract life.

Ten and a half gigawatts over nearly a decade tells me the thing I actually care about.

Microsoft isn’t hoping power shows up. Microsoft is contracting for the physical right to operate.

In July 2025, Brookfield announced a hydro framework agreement with Google for up to 3,000 megawatts, with initial contracts for 670 megawatts from Holtwood and Safe Harbor in Pennsylvania on 20-year terms. The figure attached to it was $3 billion of contracted revenue tied to those initial contracts.

Twenty years is not optionality. It’s a scarcity response.

What does that prove in plain English?

Duration is a signal of seriousness. It’s a company telling you it would rather lock the input than gamble on the spot market of the future.

Then there’s the deal that changed the texture of this for me.

In October 2025, NextEra announced the Duane Arnold nuclear restart deal with Google Cloud. The numbers attached were 615 megawatts electric, a 25-year power purchase agreement, and estimated revenue of $80 to $100 million annually when online.

That’s not what buyers do when the input is abundant and fungible.

That’s what buyers do when their roadmap assumes reliability and they don’t want to be the person who explains to the board why a billion-dollar campus can’t energize.

In December 2025, NextEra also announced 11 power purchase agreements plus 2 energy storage agreements with Meta totaling 2.5-plus gigawatts, with commissioning timelines listed as 2026 to 2028.

Step back and look at the pattern rather than the individual deals.

Long duration. Large scale. Named counterparties. Storage layered in. Commissioning windows that line up with real build schedules.

That combination is stronger evidence than any press-release target.

It’s tempting to talk about “power” like it’s a single pipe. More generation equals solved.

That’s not how this works.

The bottleneck is stacked. Generation is one layer. Delivery is another. Equipment is another. Construction capacity is another. Interconnection rights are another. Each layer can bind, and when multiple bind at once, the entire system slows.

So the real question isn’t “is there enough electricity in the abstract?”

The real question is “can you deliver firm power to that campus, on that timeline, with equipment that exists, through a queue that clears?”

That’s where projects slip. Quietly. Repeatedly.

In semiconductors, the most valuable asset often isn’t the chip. It’s the place in line at the foundry. Capacity reservation becomes the weapon.

Power infrastructure is starting to rhyme.

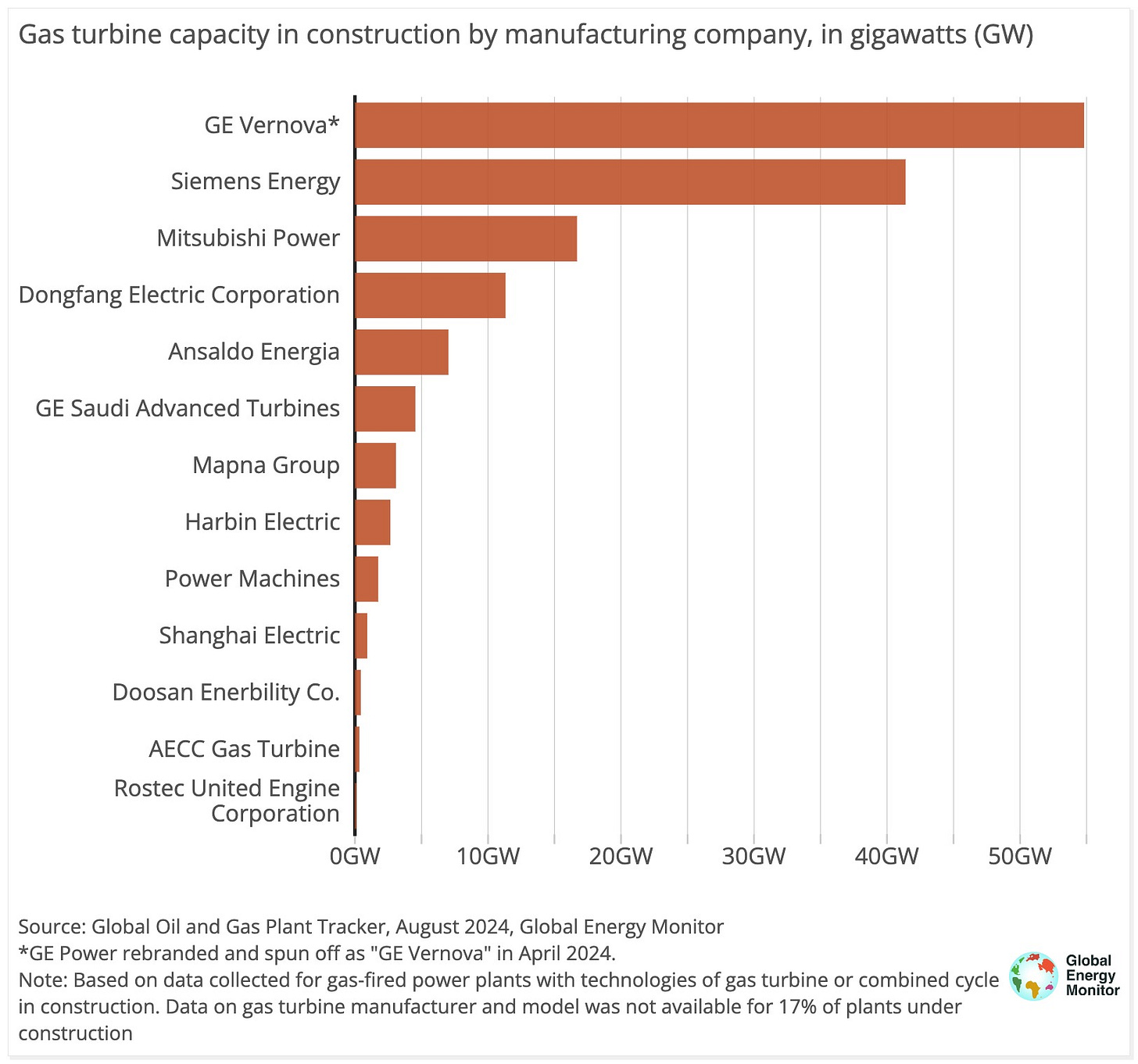

GE Vernova’s disclosures show gas turbine slot backlog moving from 45 gigawatts in the third quarter of 2024 to 62 gigawatts in the third quarter of 2025, broken into 33 gigawatts of firm orders and 29 gigawatts of slot reservation agreements backed by non-refundable payments.

Non-refundable payments for a slot.

The moat is a place in line.

And it’s not only turbines. GE Vernova’s electrification segment showed orders of $5.1 billion in the third quarter of 2025, up 102 percent organically year over year, and hyperscaler data center orders of $900 million year-to-date versus $600 million in all of 2024.

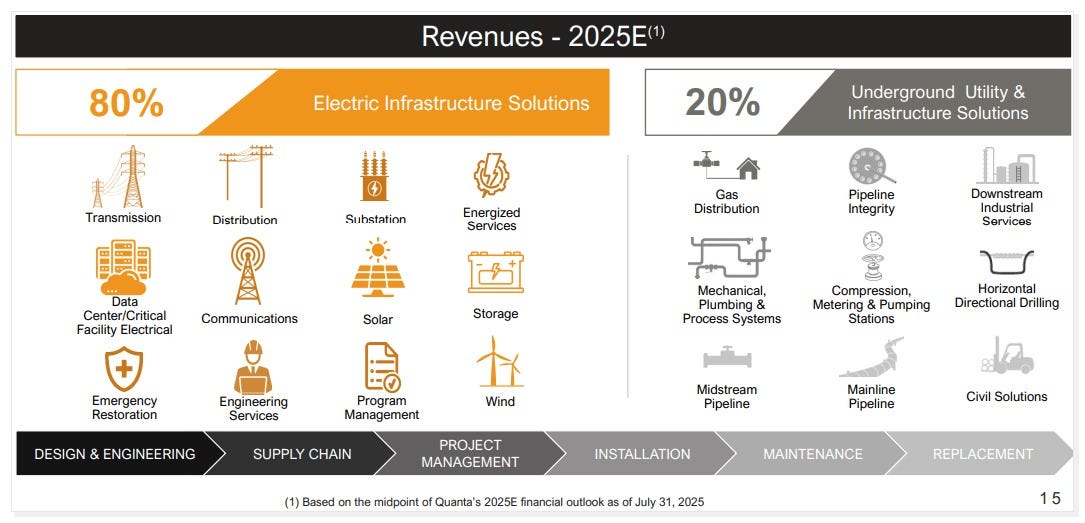

Then look at the builders. Quanta Services reported record backlog of $39.2 billion in the third quarter of 2025, up 15 percent year over year, with 40 to 50 percent of backlog now from data center power infrastructure projects. Book-to-bill was listed at 1.8 times.

I don’t need to romanticize any single number. I just need to see the shape.

Backlog is what happens when demand outruns the ability to deliver. Book-to-bill is what happens when orders show up faster than capacity to fulfill.

This is stacked scarcity. Not a single pinch point. A system with multiple pinch points.

Time-To-Power

In a normal market, price dominates. In a constrained market, speed dominates.

Who wins a hyperscaler contract when the campus timeline is 24 months?

The firm that can deliver within the timeline.

Who loses?

The firm that needs 60 months and shows up to the bid with a beautiful price.

In constrained regimes, slow suppliers don’t lose on price. They get screened out before they can quote.

Capital Power is a clean illustration of the speed premium. On December 10, 2025, it announced a binding memorandum of understanding to supply 250 megawatts to an unnamed investment-grade data center developer in Alberta, on a 10-plus year term, with an expected start date of 2028.

The key signal is that buyers are contracting far ahead of commissioning because near-term deliverability is constrained.

The same day, Capital Power announced a $3 billion partnership with Apollo, with Apollo committing $2.25 billion and Capital Power committing $750 million to pursue U.S. natural gas acquisitions.

I don’t know whether Capital Power specifically is the right vehicle to own that speed premium. The MOU still needs to convert to a final contract.

But the concept is durable.

Time-to-power is becoming the product.

The trade isn’t “buy AI.”

The trade is “underwrite the enabling constraints AI can’t scale without.”

That means prioritizing businesses paid on contracts, backlog, and delivery. Not hope, demos, and narrative multiples.

If the application layer monetizes perfectly, demand rises and the constraint tightens. If monetization disappoints, data centers still exist, and long-duration power agreements still cash flow, at least as structured in the deals described above.

That’s why the enabling layer can matter even when the software layer gets messy.

Falsifiers And Tripwires

A thesis without falsifiers is just a belief system.

Here’s what would change my view, stated as tripwires I can actually monitor.

First, sustained hyperscaler buildout contraction. Not pacing. Not optimization. Actual multi-quarter contraction that reduces signed demand in a way that shows up in cancelled or deferred power agreements. Does the pipeline shrink materially?

Second, regulatory caps that prevent utilities from capturing any data center premium. Do regulators constrain returns tightly enough that structural importance doesn’t translate to earnings acceleration?

Third, equipment backlog unwind. If turbine slot reservations and electrification backlogs reverse quickly, was this a temporary rush rather than a durable scarcity regime?

Fourth, multiple rerate without earnings. If the enabling layer gets repriced upward before the cash flow shows up, the easy part of the setup is gone. Does valuation change before fundamentals do?

None of these falsifiers feel more likely than the base case to me. But they’re real, and they’re watchable.

Indicators I’m Watching

I’m not trying to predict a date. I’m trying to watch the system tell the truth.

I’m watching earnings call language from utilities, independent power producers, grid builders, and power equipment manufacturers. Are they explicitly citing data center backlog? Are they talking about interconnection timelines and equipment availability? Are they describing time-to-power as a competitive advantage?

I’m watching contract behavior. Are counterparties still signing long-duration agreements at scale? Are terms extending? Are storage and firming becoming standard?

I’m watching slot reservation behavior. Do non-refundable slot reservations persist and expand, or does that urgency fade?

And I’m watching regional grid stress narratives as a watch item, not a prediction. Are operators and regulators signaling rising strain in places like ERCOT? Do interconnection queues and commissioning timelines become part of mainstream guidance?

Those are habit-forming signals. They’ll tell me whether the constraint is tightening or loosening.

The Takeaway

The next Nvidia probably won’t look like Nvidia. It might look like a utility signing 20-year contracts. It might look like a turbine manufacturer selling years of slots in advance. It might look like a grid contractor sitting on record backlog because substations and transmission are now the schedule.

That’s usually what the best setups look like before the narrative catches up.

AI doesn’t need more adjectives.

It needs electricity.