The AI Chip War's Hidden Winner

Google, Amazon, and Nvidia are locked in a silicon arms race. The actual beneficiaries couldn't care less who wins.

Google wants to sell you chips it spent a decade keeping to itself. Amazon just launched silicon you can only rent through AWS. Both companies are pitching these as alternatives to Nvidia’s GPUs, and the headlines write themselves: challenge to Nvidia dominance, hyperscalers fight back, the end of the GPU monopoly.

When I traced the actual specifications, customer targets, and supply chains, the story stopped looking like a clean “Nvidia killer” narrative and started looking like something more constrained and more interesting. Google’s TPU push is real, but Google’s own ambition is more modest than the rhetoric. Amazon’s Trainium is powerful, but it’s also fenced inside AWS by design. And the companies that make, connect, power, and cool all this hardware are positioned to win regardless of which chip runs any given model.

The contradiction that kept coming up is simple: the loudest claims are about replacing Nvidia, but the behavior I see is about fragmenting specific workloads and reducing dependence, not overthrowing an ecosystem. In that frame, Nvidia is not the obvious casualty. AMD is.

From here, the question I care about isn’t “who kills Nvidia?” It’s “where do these custom chips actually compete, where do they not, and who gets paid either way?”

What TPUs Actually Do

Google’s Tensor Processing Units did not appear because Nvidia got expensive in 2024. They were born out of a much older problem: Google’s internal neural network workloads were growing faster than general-purpose compute could handle efficiently.

The development arc is long enough that it changes how I interpret today’s TPU headlines. According to a TPU development history, Google originated the TPU effort in 2013 and had TPU v1 deployed in data centers by 2015, where it delivered ”15-30x better performance per watt than contemporary CPUs/GPUs for inference” for the workloads it was designed to run. That is not a speculative science project. That’s a mature internal platform that spent years being hardened under production load.

Google then did something that looks obvious in hindsight but is strategically delicate: it began making TPUs available outside the company, gradually. The externalization didn’t happen all at once. TPUs arrived in Google Cloud in stages, including TPU v3 availability in 2018 and later generations. By April 2025, Google was publicly discussing Ironwood, described as TPU v7, as part of its specialized AI chips story. The key point is not the naming. It’s the direction of travel: Google is turning an internal advantage into a product.

That’s where the “Nvidia killer” framing starts to wobble.

A third-party industry analysis captured the mood shift around the latest generation with a blunt line: ”First real competition Nvidia felt”. I understand why that phrasing travels. TPU v7 is not a toy, and Google has the scale to put serious volume behind it.

But when I kept pulling on that thread, I ran into Google’s own internal expectations, which are far more restrained than the hype cycle suggests.

Morgan Stanley projects that 500,000 external TPUs could add $13 billion to Alphabet’s revenue by 2027. That’s a meaningful number. It implies Google believes it can sell TPU capacity well beyond its own internal needs, and that there’s a real market for it.

Then comes the number that changes the tone of the entire conversation: the same item reports Google’s long-term internal goal is capturing 10% of Nvidia’s data center revenues.

Ten percent.

That figure doesn’t read like a company preparing to topple a monopoly. It reads like a company executing a flanking maneuver: take the slices of the workload pie where a purpose-built accelerator wins on cost and efficiency, and leave the rest to the platform that already runs everything.

Google’s own positioning around TPU strengths supports that narrower interpretation. In its discussion of TPU history and generative AI, Google argues that TPUs outperform GPUs by 50-100% per dollar or per watt for certain categories, including high-volume inference, large training, and recommendation workloads. That’s a specific workload list, and it matters.

Inference is the act of running a trained model in production, serving user queries. Recommendation systems are high-throughput, latency-sensitive, and core to ad-driven platforms. Large training is the expensive frontier where big labs burn capital to create new model capabilities. If TPUs are meaningfully better on those axes, that’s a real competitive wedge.

But it’s also a wedge that depends on the workload matching the chip’s design assumptions and Google’s software stack. That’s the part the “killer” framing tends to skip. The TPU story is not “general compute replacement.” It’s “specialization at scale.”

I kept coming back to the 10% target because it forces a more honest reading: Google can win big in absolute dollars while still leaving Nvidia’s ecosystem intact. And if that’s true, the next question isn’t whether TPUs are good. It’s who is actually buying them, and why.

That takes me to the most revealing piece of the TPU commercialization story: the customers.

Meta’s Billion-Dollar Hedge

The cleanest signal in this market is not a product launch. It’s a commitment from a buyer with enough scale to matter.

Google has one of those in hand. In an October 2025 announcement, Google Cloud said Anthropic will expand its use of Google Cloud TPUs and services, with access to up to 1 million TPUs. “Up to” is an important qualifier, but the ceiling is the story. At that magnitude, we’re no longer talking about a niche alternative. We’re talking about a second industrial supply line for frontier-scale AI compute.

Anthropic’s move also clarifies how Google is trying to commercialize TPUs. Google is not merely selling chips as components. It is selling an integrated environment: TPU hardware, Google Cloud infrastructure, and the software stack that makes TPUs usable at scale.

Then there’s the deal that isn’t a deal yet, but is analytically hard to ignore.

Reuters reported in November 2025 that Meta is in talks to spend billions on Google’s chips, with purchases potentially starting in 2027. This remains genuinely unclear in the way many hyperscaler negotiations are unclear until contracts are signed: timelines shift, volumes change, and public confirmation often comes late if it comes at all. But the logic of the talks is straightforward once you look at Meta’s spending trajectory.

Reuters also reported that Meta’s AI infrastructure capex is $70 billion this year, with projections near $100 billion in 2026. At $70 billion to $100 billion per year, vendor concentration becomes a board-level risk issue, not a procurement detail. If you are building that much AI infrastructure, you don’t want a single supplier to dictate pricing, delivery schedules, or product cycles.

Meta has also been developing its own chips, but the Reuters framing around diversification aligns with a broader reality: internal chips rarely eliminate the need for external capacity when demand is exploding. Even if Meta’s internal efforts cover a slice of inference, frontier training is a different beast, and scaling it requires proven cluster designs.

This is where Google’s infrastructure history matters. Google points to established 10,000-TPU pods for training frontier models. That number is not just a flex. It’s a clue about operational maturity: Google has been running large TPU clusters long enough to have standardized the architecture and the operational playbook.

If I’m Meta, staring at a capex curve that steep, I don’t need to believe TPUs replace Nvidia everywhere. I just need to believe TPUs can reliably absorb a meaningful fraction of training and inference demand at a better cost profile, while giving me leverage in negotiations with every other vendor.

That’s why I think of this as a hedge, not a coup. Meta’s reported interest, if it turns into a real purchase program, would say less about Nvidia’s weakness and more about hyperscalers doing what hyperscalers do: multi-source critical inputs, avoid lock-in, and optimize per workload.

It also sets up the next piece of the puzzle. If Google is trying to sell TPUs externally, why aren’t other hyperscalers lining up as customers?

In practice, the biggest reason is simple: Microsoft and Amazon are not waiting for Google to supply their compute future. They’re building their own.

Amazon’s Parallel Track

Amazon’s approach to custom silicon is almost the mirror image of Google’s.

Google is externalizing a chip family that was built for internal needs and then productized for Google Cloud customers. Amazon is building custom chips that, by design, you don’t buy at all. You rent them as instances inside AWS.

In December 2025, AWS announced new EC2 Trn3 UltraServers and described the Trainium 3 leap in its own words:

“Trn3 delivers up to 4.4x higher performance, 3.9x higher memory bandwidth and 4x better performance/watt vs Trn2”

Those are aggressive generational claims, and they map to the physics constraints that matter for modern AI. Memory bandwidth is often the bottleneck for large model training and inference. Performance per watt is not a marketing metric; it’s a data center design constraint.

HPCwire added concrete hardware detail to that performance framing, reporting that Trainium 3 includes 144GB of HBM3e memory capacity, described as 50%+ more than the previous generation, and 4.9TB/s bandwidth, described as 70%+ more. Those numbers are the kind of improvements that can change unit economics for large-scale deployments.

The strategic detail that matters just as much as the specs is the distribution model. AWS’s own announcement makes clear that Trainium 3 is available only via AWS EC2 instances, not sold externally. Amazon is not trying to create a merchant chip business. It is trying to lower its own cost of goods sold for AI compute, differentiate AWS offerings, and keep customers inside its cloud.

That means Trainium competes most directly with Nvidia and AMD inside AWS, where Amazon controls the platform, the orchestration, and the pricing model. It also means Trainium doesn’t need to win the broader ecosystem war. It only needs to be “good enough” on the workloads Amazon cares about most, at a better cost structure, so AWS can price competitively and protect margins.

This is the pattern I see across hyperscalers: they’re not trying to become Nvidia. They’re trying to stop being price takers for the most expensive line item in their AI stack.

But the moment you say that out loud, you run into the next reality: there are still many workloads where specialization is a tax, not a benefit.

That’s where Nvidia’s moat shows up, and it’s deeper than a single chip generation.

The CUDA Moat

Nvidia’s advantage is often described as “GPUs are faster” or “Nvidia has better hardware.” That’s not wrong, but it’s incomplete. The more durable advantage is that Nvidia is a platform, and platforms win by making it cheap for developers to build and migrate across workloads.

Jensen Huang captured Nvidia’s confidence in a sentence that is designed to sound like a compliment and land like a warning. Responding to TPU competition and the broader custom chip trend, Huang said:

“Nvidia is the only platform that runs every AI model”

The reason that statement has bite is that it’s not merely about LLMs. Nvidia’s GPU stack is used across a wide range of AI and adjacent compute tasks. CNBC summarized that breadth in a way that’s useful precisely because it’s not mystical. Nvidia GPUs are used for LLMs, image and video generation, physics simulation, visualization, product design, protein folding, drug discovery, robotics, and self-driving.

That list matters because it highlights the real boundary of custom ASIC competition. TPUs and Trainium can be excellent at specific workloads, but many organizations don’t run a single workload. They run a portfolio. They want one infrastructure layer that can serve multiple teams: research, production inference, simulation, and domain-specific pipelines.

That’s where CUDA becomes a moat rather than a feature. A CUDA ecosystem analysis describes a developer base of 3.5 million developers and 600+ libraries. Those numbers are not just vanity metrics. They represent switching costs, accumulated tooling, and a shared language across the AI engineering world.

Even if a TPU or Trainium system is cheaper for a given workload, the organization has to ask: what is the cost of retraining engineers, porting code, validating performance, and maintaining two stacks? The answer varies, but it is rarely zero.

This is where I think the “chip wars” framing misleads. The war metaphor implies a single front and a single victor. The reality looks more like workload segmentation.

For hyperscalers, segmentation is a feature. They can run multiple stacks because they have the engineering capacity and the scale to justify it. For many enterprises, segmentation is a burden, which keeps Nvidia’s generality attractive.

And even for hyperscalers, segmentation has limits. Google’s own internal goal of 10% of Nvidia’s data center revenues reads to me like an admission that CUDA’s breadth is hard to displace. Google can win slices where TPUs offer a 50-100% advantage per dollar or watt, but it doesn’t expect to become the default platform for everything.

Nvidia also isn’t standing still. CNBC notes Nvidia’s role as the manufacturer of GPUs like Blackwell while other hyperscalers develop custom chips. Nvidia’s platform posture is increasingly about being the universal substrate: if you want to run anything, you can run it on Nvidia.

So if Nvidia isn’t the obvious loser, who is?

The uncomfortable answer is the company that positioned itself as the “cheaper Nvidia alternative” right as hyperscalers began building “cheaper than Nvidia” alternatives of their own.

AMD in the Crossfire

AMD’s AI story has often been framed as the pragmatic alternative: similar outcomes at lower cost, especially for high-volume inference where the economics matter and the cutting edge is not always required.

That positioning is rational. It is also exactly where hyperscaler ASICs aim.

In 2025 commentary about custom ASIC competition, AMD CEO Lisa Su offered a concise defense of the GPU model:

“GPUs dominate due to flexibility”

I don’t think Su is wrong. Flexibility is a real advantage, and it’s part of why Nvidia’s platform is so sticky. But the line also exposes AMD’s problem. The workloads AMD most wants to capture, especially cost-sensitive inference, are often the workloads where flexibility matters least.

If your inference workload is stable, high-volume, and well-understood, the winning chip is frequently the one that delivers the lowest cost per token or per query within acceptable latency and reliability. That is precisely the domain where Google claims TPUs can outperform GPUs by 50-100% per dollar or watt, and where Amazon is pushing Trainium’s performance per watt improvements.

The collision gets more specific when you look at where these chips live.

TPUs compete most directly in Google Cloud, and the customer signals I’ve already discussed include Anthropic’s access to up to 1 million TPUs and Meta’s reported talks. If TPUs become a standard option for major AI labs and large buyers inside Google Cloud, that’s not just pressure on Nvidia. It’s pressure on any alternative GPU supplier trying to win cloud inference and training share.

Trainium is even more direct: it reduces the need for AMD in AWS because Amazon can steer customers toward Trainium instances for the workloads Trainium handles well. AWS doesn’t need to ban GPUs; it just needs to make the economics attractive enough that customers choose Trainium for a meaningful fraction of usage.

In other words, Nvidia’s moat is platform breadth and developer lock-in. AMD’s wedge is often price-performance in a narrower band. Custom ASICs are designed to attack that narrower band.

This is the irony I can’t shake: the chips framed as Nvidia challengers may end up compressing AMD’s opportunity more than Nvidia’s, because AMD’s “value” proposition overlaps with the custom chip rationale, while Nvidia’s “platform” proposition is harder to replicate.

Once you see that, the rest of the story becomes less about a single winner and more about a supply chain that gets paid no matter which silicon is running the workload.

That’s where the real structural winners sit.

The Infrastructure Layer

When I mapped the AI chip landscape across Nvidia, Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta, the most important observation wasn’t about whose chip is faster. It was about who sits underneath all of them.

CNBC put the manufacturing reality plainly: TSMC manufactures Nvidia GPUs (including Blackwell), Google TPUs, Amazon Trainium, Microsoft Maia, and Meta MTIA. If you care about who benefits from chip proliferation, that one fact is the spine of the story.

The implication is geopolitical as much as it is commercial. Every major AI chip strategy, whether it’s Nvidia’s merchant GPU model or hyperscaler vertical integration, still routes through the same advanced manufacturing choke point.

Custom chips do not remove dependence. They relocate it.

They also increase demand for advanced manufacturing and packaging. This is where the story gets uncertain in a way that matters: the ramp of any custom chip program is not just a design question, it’s a capacity question. The situation is more ambiguous than the headlines suggest because the limiting factor can be packaging and manufacturing throughput, not customer demand.

That matters because it means the “chip wars” are constrained by the same industrial bottleneck. The more custom chips hyperscalers design, the more they compete with each other for the same underlying capacity.

Then there’s the networking layer, which is less glamorous than GPUs but just as binding at scale.

An industry analysis describes Broadcom as holding approximately 90% market share in Ethernet switching chips for data centers. It also states that 30% of AI workloads currently run on Ethernet, and that share is growing. In practice, whether your compute runs on Nvidia GPUs, Google TPUs, or Amazon Trainium, it still needs to be connected into clusters, moved across racks, and fed with data. Broadcom’s dominance in Ethernet switching means it captures value from the “plumbing” of AI regardless of which compute chip wins any given benchmark.

Broadcom also shows up in the chip design ecosystem. CNBC notes Broadcom’s role in the broader AI chip landscape in a way that aligns with its reputation as a key enabler of custom silicon programs. The more hyperscalers pursue custom accelerators, the more valuable the specialized design and networking ecosystem becomes.

Finally, there’s the physical reality that makes performance per watt more than a marketing line.

Vertiv, a major supplier of data center power and cooling infrastructure, notes that electricity is approximately 1/3 of data center operating expenses, and cooling is 40% of that. That’s the economic reason hyperscalers obsess over efficiency. If you can improve performance per watt, you’re not just saving energy. You’re changing how many racks you can deploy per megawatt, how dense you can pack compute, and how fast you can scale within power constraints.

Vertiv also points to the hardware consequences of that density push, citing liquid cooling capacity of 600kW per unit for high-density racks. That number is a reminder that the AI buildout is not just a chip story. It’s a facilities story. Power delivery, thermal management, and cooling infrastructure become first-order constraints as racks get denser.

Put these pieces together and the “who wins” narrative shifts.

If more AI chips are produced, TSMC benefits because it manufactures across the entire competitive set.

If more clusters are built and more AI workloads ride Ethernet, Broadcom benefits because it dominates switching and the networking layer scales with compute.

If racks get denser and power becomes a larger share of operating expense, Vertiv benefits because cooling and power infrastructure scale with the physical buildout.

This is why I don’t think the chip wars are a single elimination tournament. The infrastructure layer is a toll road. It gets paid regardless of which logo is stamped on the silicon.

And that brings me to the macro context that makes this a positive-sum contest for most of the major players.

The Expanding Pie

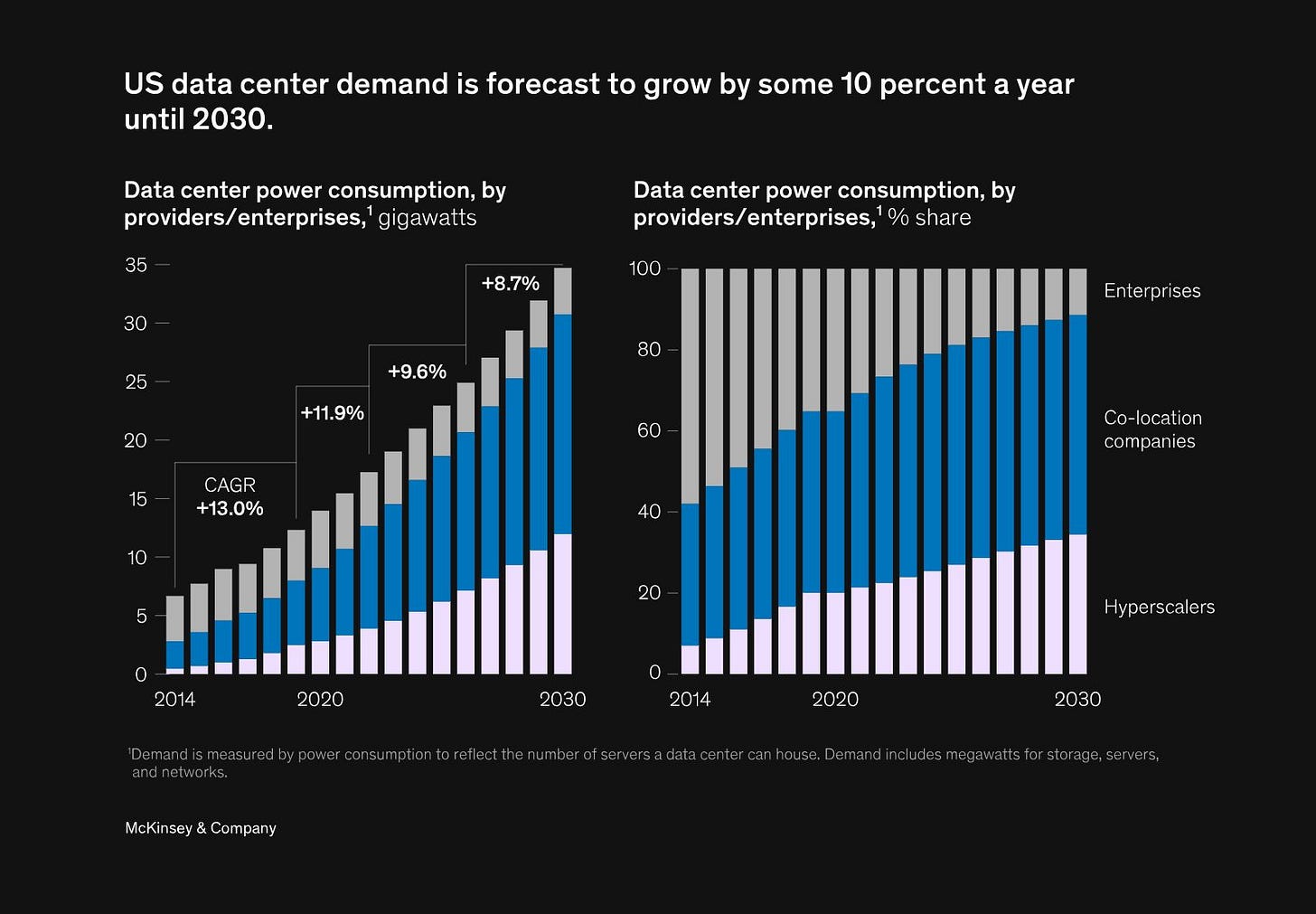

The reason multiple strategies can coexist is that the market is growing fast enough to support multiple winners.

Statista projects the AI market will grow at 37% CAGR to $1.68 trillion by 2031. At that growth rate, the market is not fighting over a fixed pie. It’s racing to build capacity fast enough to meet demand.

That growth spans more than LLM chatbots. It includes categories like natural language processing, computer vision, and the broader set of autonomy and robotics-adjacent workloads that Nvidia’s GPU ecosystem already serves. Nvidia’s flexibility and CUDA platform advantage align with a market that is broadening, not narrowing.

At the same time, hyperscalers have rational incentives to diversify. If you’re spending tens of billions per year like Meta, you want leverage, redundancy, and workload-specific optimization. Custom chips can erode Nvidia’s pricing power in the segments where they compete most directly, especially LLM training and high-volume inference. But erosion of pricing power in a subset of workloads is not the same thing as displacement of the overall platform.

This is the deeper reason the “Nvidia killer” framing falls apart. The market is expanding so quickly that hyperscalers can build custom chips, continue buying Nvidia at massive scale, and still not satisfy total demand. Competition becomes a way to allocate workloads efficiently, not a way to eliminate a supplier.

In that environment, the most interesting question is not “who wins the war?” It’s “what does this fragmentation do to bargaining power, margins, and the companies caught between platform dominance and hyperscaler vertical integration?”

That’s where the synthesis lands.

What This Really Means

The “chip wars” metaphor obscures more than it reveals. When I line up what hyperscalers are doing with what they are saying, I see a pattern of optimization and hedging, not a coordinated effort to dethrone Nvidia.

Google is the clearest example. It is positioning TPUs as an external product, and Morgan Stanley’s projection of 500,000 external TPUs adding $13 billion to Alphabet revenue by 2027 shows real ambition. But Google’s own internal goal of 10% of Nvidia’s data center revenues is the tell. Google is not underwriting a world where TPUs replace CUDA everywhere. It’s underwriting a world where TPUs win the workloads they’re best at and monetize that advantage through Google Cloud.

Amazon’s approach is even more explicit. Trainium 3’s generational jump, described by AWS as ”up to 4.4x higher performance, 3.9x higher memory bandwidth and 4x better performance/watt vs Trn2”, is a statement about cost structure and control. But Amazon keeps Trainium inside AWS. That’s not a merchant chip play. It’s vertical integration for cloud economics.

Nvidia, meanwhile, is defending a different hill. Huang’s line, ”Nvidia is the only platform that runs every AI model”, is a reminder that the platform story is bigger than LLMs. CUDA’s 3.5 million developers and 600+ libraries are the practical moat behind that claim. Custom chips can win narrow workload bands, but they don’t easily replicate the breadth of a general platform used across robotics, simulation, drug discovery, and self-driving.

The company that looks most pressured in this setup is AMD. Lisa Su’s defense that ”GPUs dominate due to flexibility” is true, but it also highlights the trap: AMD’s growth narrative has leaned on being a cheaper alternative for inference, and inference is exactly where custom ASICs are most economically compelling. Nvidia has a platform moat above. Hyperscalers have vertical integration below. AMD sits in the middle.

If I step back and ask who benefits regardless of which silicon wins individual workloads, the answer is the infrastructure layer.

TSMC manufactures Nvidia GPUs, Google TPUs, Amazon Trainium, Microsoft Maia, and Meta MTIA. Proliferation of chips still routes through Taiwan.

Broadcom dominates data center Ethernet switching with approximately 90% market share, and an industry analysis notes 30% of AI workloads currently run on Ethernet and that share is growing. More compute means more networking.

Vertiv sits downstream of all of it, in the physical layer where electricity is about 1/3 of data center opex and cooling is 40% of that, and where liquid cooling capacity is scaling toward 600kW per unit. More AI means more power and cooling, regardless of whose chip is inside the rack.

There are uncertainties that matter, and they’re structural.

It remains genuinely unclear whether Meta’s reported talks turn into a signed, scaled TPU purchase program starting in 2027, and at what volume. It’s also unclear how manufacturing and packaging constraints shape the ramp of custom chips across the industry, because all roads lead to the same manufacturing base. And it’s uncertain how Nvidia responds on pricing in the LLM-focused segments where alternatives exist, because Nvidia can choose to defend volume even if it compresses margins.

The falsifiers are straightforward.

If Google starts talking about a target materially above 10% of Nvidia’s data center revenues, that would signal a strategy shift from flanking to frontal assault. If a major hyperscaler like Microsoft or Amazon were to buy Google TPUs, it would imply a new kind of cross-cloud compute alliance that currently looks strategically awkward. And if AMD were to announce significant custom ASIC design wins for inference workloads, it would suggest AMD is pivoting into the very game that’s pressuring it.

Until then, I think the right mental model is coexistence: custom chips carve out slices, Nvidia remains the universal platform, and the infrastructure layer collects tolls.

The Close

The headlines will keep calling these chips “Nvidia killers.” They’re not. Google knows it, which is why its internal ambition is framed around 10% of Nvidia’s data center revenues. Amazon knows it, which is why Trainium stays inside AWS. Hyperscalers are optimizing specific workloads while continuing to buy Nvidia at massive scale, because ecosystems don’t get replaced overnight. They get routed around.

The companies that win regardless of which chip computes the next trillion parameters are the ones manufacturing, connecting, powering, and cooling the entire stack.

Follow the supply chain, not the headlines.

I resonate with your take. What if workload fragmentation inadvertently empowers diverse smaller competitors long-term?