Oracle’s CDS Spike and the $1.4 Trillion Infrastructure Question Nobody’s Answering

When Infrastructure Spending Outpaces Revenue by 100x

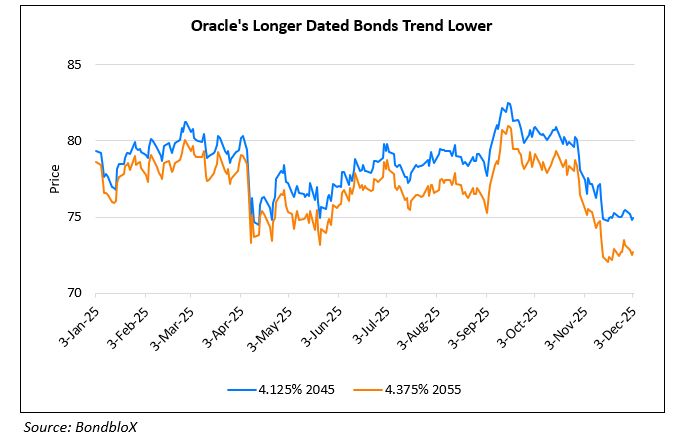

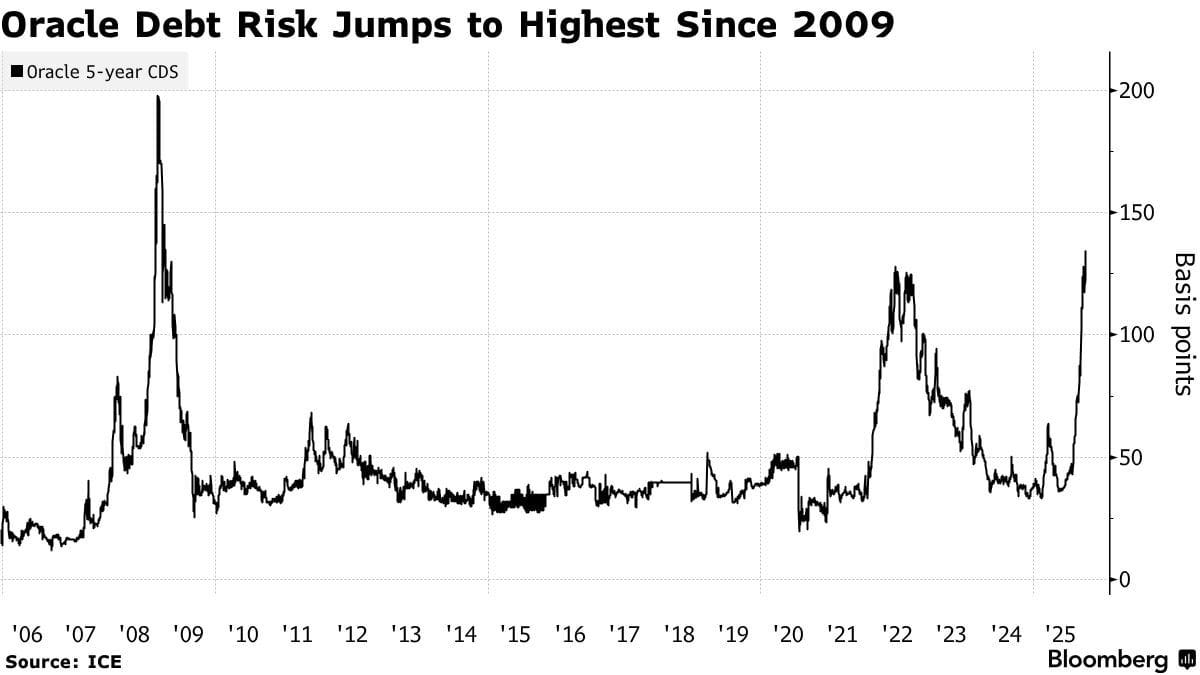

Oracle’s five-year credit default swaps hit 139 basis points in December 2025. Highest level since the financial crisis.

Oracle is not “going bankrupt.” That’s not what this is.

Credit spreads do one thing really well. They sniff out counterparty risk and timing risk before equity is ready to talk about it in public. And right now the market is circling a much bigger animal than Oracle’s standalone balance sheet.

The bigger animal is this. A huge chunk of the AI infrastructure buildout is being financed and justified by revenue projections that, at least on today’s numbers, don’t come close to matching the spending schedule.

That gap is the trade.

And it’s starting to show up in places people don’t usually watch until it’s too late.

The $1.4 trillion question

Here’s the math I can’t get out of my head.

OpenAI generated roughly $13 billion in revenue in 2025. The company has committed to $1.4 trillion in infrastructure spending through 2033. That’s about $175 billion a year.

So the infrastructure commitment is around 108 times current annual revenue.

That ratio doesn’t mean “fraud” or “collapse.” It means dependency. It means everything downstream of that commitment is implicitly betting that the revenue curve shows up on time.

HSBC ran the numbers on what “showing up on time” would even require. Even if OpenAI’s consumer base grows from 10 percent to 44 percent of the world’s adult population by 2030, HSBC still sees a $207 billion funding shortfall. Cumulative free cash flow stays negative through the decade. Cloud and infrastructure costs alone total $792 billion between now and 2030. Total compute commitments reach $1.4 trillion by 2033.

So what’s actually being priced isn’t “will OpenAI exist.” It’s “how tight does the funding loop get if the revenue line doesn’t come in fast enough.”

Because if the revenue doesn’t steepen fast enough, the whole chain has to reprice.

Semiconductor suppliers. The private credit desks funding data centers. Hyperscalers building capacity. Venture capital funding the application layer on top. Everybody is living off the same assumption, whether they admit it or not.

Proprietary AI models will generate enough cash to justify infrastructure that currently costs around 100 times more than what those models bring in.

The market is starting to notice the gap.

The infrastructure boom that ate Singapore’s GDP

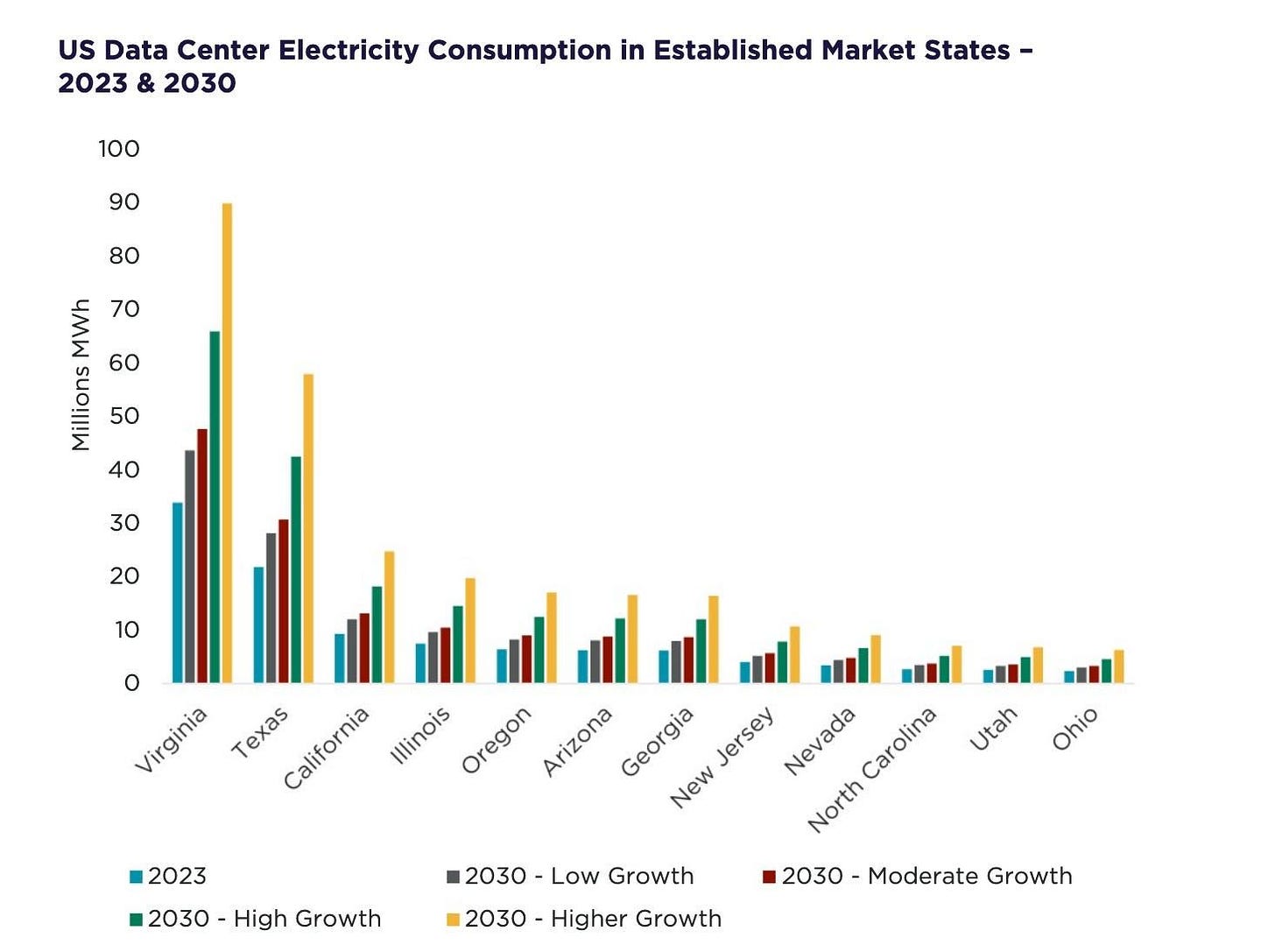

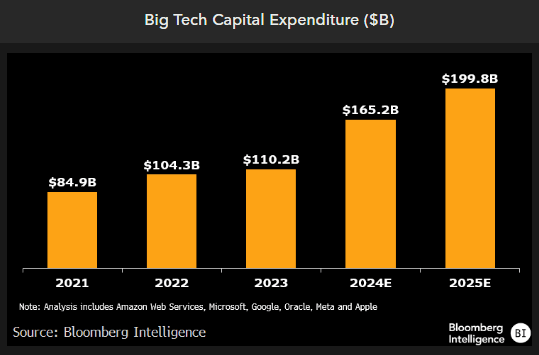

Total AI capital expenditures in the US are projected to exceed $500 billion in both 2026 and 2027. Roughly Singapore’s entire annual GDP. Every ten months.

When I sanity-check that scale, I keep coming back to old reference points. The Apollo program spent approximately $280 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars over a decade. Right now, we’re on a path to do that annually, with no defined endpoint.

It gets clearer when you stop talking in aggregates and start looking at the individual commitments.

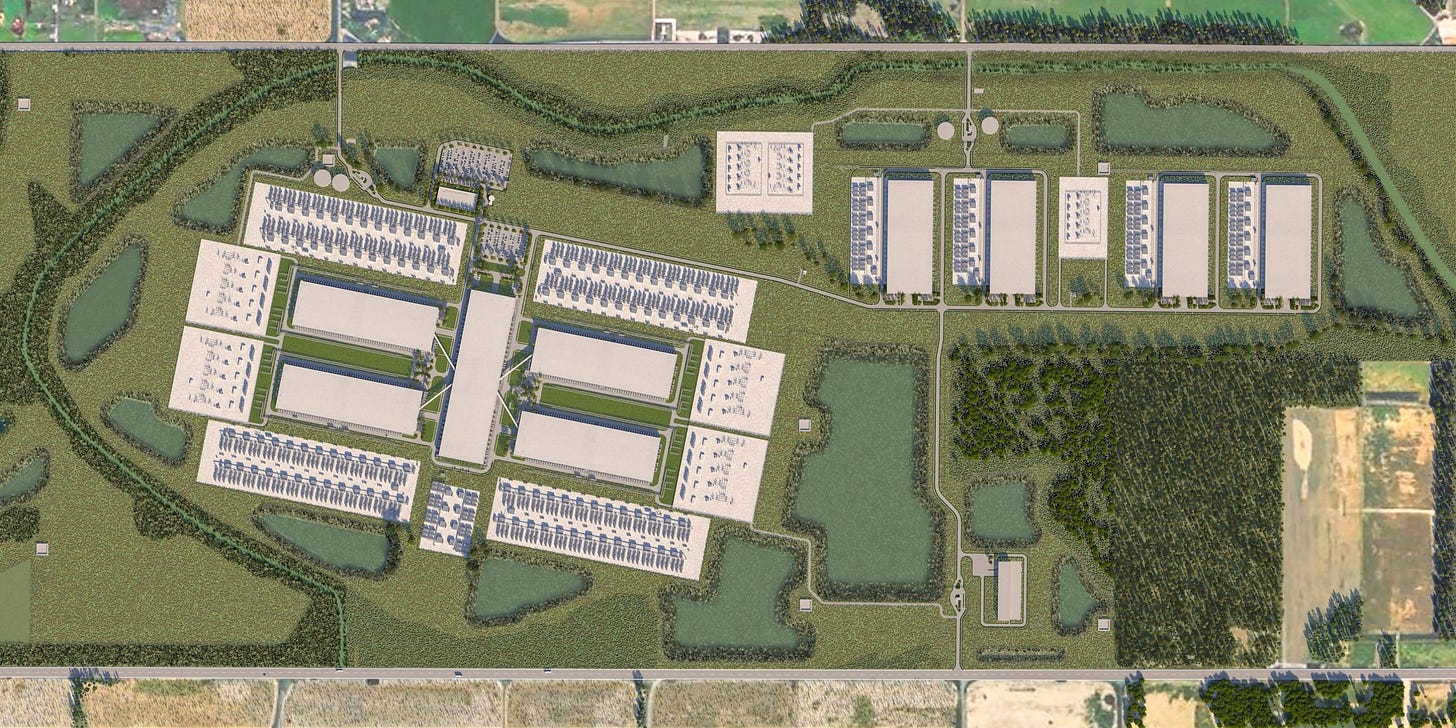

OpenAI’s Stargate project launched in January 2025 with $100 billion, targeting $500 billion by 2029. By September, OpenAI had announced five new data center sites spanning nearly 7 gigawatts of planned capacity and over $400 billion in committed investment. The partnership with Oracle alone exceeds $100 billion, with Oracle displacing Microsoft as the primary infrastructure builder.

Then you have Meta.

Meta closed a $27 billion financing for its Hyperion data center campus in Louisiana. Largest private credit transaction ever executed. The structure is clean. Meta retains 20 percent equity while Blue Owl-managed funds hold 80 percent. PIMCO anchored the debt with $18 billion. BlackRock contributed $3 billion in equity. The bonds priced at 225 basis points over Treasuries, about double the spread on Meta’s own corporate bonds.

If you want the template for how this cycle is getting funded, that deal is it.

Convert capital expenditure into operating expense. Keep the balance sheet pretty. Transfer tech risk back onto the sponsor through guarantees. Pull insurance-grade capital into the stack through structured debt.

It’s impressive engineering.

It’s also a way of saying, quietly, that the buildout is too large to fund the old way.

Paul Kedrosky notes that data center-related spending in the first half of 2025 probably accounted for half of GDP growth in that period. His phrase was “absolutely bananas.”

He’s not wrong.

And when you look under the hood, the spending is even more concentrated than most people realize. For the largest companies, about 60 percent of data center costs are GPU chips. The rest is cooling, power equipment, and then relatively small construction components.

So you get a very specific kind of concentration risk.

Nvidia holds over 90 percent market share in data center GPUs. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company manufactures Nvidia’s most advanced chips. TSMC’s chief executive has said AI demand is “insane” and accelerating faster than expected.

One company. One island. One process node.

That’s what the entire AI infrastructure boom is really sitting on.

And the combined scale of Stargate and Hyperion alone approaches 12 gigawatts of planned capacity. Roughly twelve nuclear reactors.

This is where the dependency chain becomes the story.

If OpenAI can’t fund chip purchases, AMD’s revenue projections don’t just get a haircut. They break. If infrastructure returns disappoint, private credit spreads widen. If credit conditions tighten, new projects don’t pencil. If new projects don’t pencil, suppliers miss their own ramp assumptions.

It’s not one domino. It’s a row of dominoes holding hands.

The commoditization problem nobody wants to talk about

When credit starts moving before equity, it’s usually not reacting to product vibes. It’s reacting to economics.

And the economics question sitting under all of this is simple.

What happens if the model layer becomes cheap?

China now leads in 66 of 74 critical technologies tracked by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. The United States leads in eight. In artificial intelligence specifically, China produces 30 percent of high-impact publications compared to 18 percent for the United States.

The direction of travel matters here. Not as a geopolitical talking point. As a pricing problem.

China is pushing open-source model development while US companies are concentrating capital into proprietary infrastructure. And when open source gets “good enough,” it doesn’t politely coexist. It turns pricing power into a negotiation.

DeepSeek released its R1 reasoning model in January 2025 and reported performance comparable to OpenAI’s o1 across mathematics, code, and reasoning tasks. The training cost was $294,000.

I’m going to be careful with what that means, because there are always footnotes in these comparisons. Training cost can be defined narrowly. Benchmarks can be selected. “Comparable” can mean a lot of things.

But even with generous caveats, that number forces the same question.

If someone can ship something in the same neighborhood for a tiny fraction of the headline spend, what exactly are we buying when we fund trillion-dollar compute commitments?

DeepSeek’s model was trained primarily on Nvidia’s H800 chips, which became forbidden from sale to China under US export controls in 2023. That detail is the point. It shows a real ability to work inside hardware limits and still land near the frontier.

DeepSeek’s approach used automated reinforcement learning to create reasoning capabilities without extensive supervised fine-tuning. The company open-sourced distilled versions at multiple parameter sizes. DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-32B outperforms OpenAI’s o1-mini across various benchmarks.

Then Europe shows up with its own version of the same move.

Mistral AI released Mistral Large 3, a mixture-of-experts model with 41 billion active parameters and 675 billion total parameters. Trained from scratch on 3,000 Nvidia H200 GPUs. Debuted at number two in the open-source non-reasoning category. Released under Apache 2.0. Free for commercial use.

Then Meta does what Meta does.

Meta released Llama 4 Scout and Llama 4 Maverick. Natively multimodal. Llama 4 Scout has a 10 million token context window and runs on a single H100 GPU. Llama 4 Maverick has 17 billion active parameters, 128 experts, 400 billion total parameters. Meta says Maverick posts best-in-class multimodal performance, exceeding GPT-4o and Gemini 2.0 on coding, reasoning, multilingual, long-context, and image benchmarks.

What matters isn’t who wins the benchmark leaderboard on a given week. What matters is the trend.

Open-source models keep moving up the quality curve while staying structurally cheaper to run and easier to distribute.

I’ve watched this movie before. When Meta released LLaMA 2 under a permissive license, derivatives appeared within weeks. Fine-tuned chatbots. Domain-specific models. Optimizations. When Mistral 7B shipped under Apache 2.0, anyone could integrate a top-tier small model into an application for free.

That’s not competition. That’s gravity.

The proprietary model business depends on maintaining enough performance advantage to justify subscription pricing, plus all the enterprise-grade extras that come with it.

Right now, there are still real edges.

GPT-4.1 shows slightly better factual reliability with a 2.8 percent hallucination rate compared to Gemini 2.5 Pro’s 3.2 percent. ChatGPT generally does better on creative tasks and ethical reasoning. Those advantages exist.

But the direction still matters.

If open source gets to parity for 80 to 90 percent of enterprise work while staying cheaper, the subscription economics don’t just get pressured. They get renegotiated. Procurement people don’t care about your mythology. They care about the bill.

And when the model layer gets cheaper, the infrastructure layer doesn’t magically get cheaper with it. Those chips are still those chips. The power draw is still the power draw. The debt still needs to be serviced.

That’s the mismatch Oracle’s CDS is quietly pointing at.

Oracle’s CDS is a symptom, not the disease

Oracle’s credit risk signals aren’t just “Oracle being Oracle.”

Oracle has material revenue concentration with OpenAI. That creates real counterparty exposure. Oracle also reported negative free cash flow of about $10 billion in recent quarters. Capital expenditures are outrunning operating cash generation.

S&P and Moody’s both downgraded Oracle’s outlook. Moody’s described Oracle as having the weakest credit metrics among investment-grade hyperscalers. Bloomberg reported that Oracle pushed back completion of some OpenAI data centers from 2027 to 2028 due to labor and material shortages.

And credit analysts are now saying the quiet part out loud.

Barclays and Morgan Stanley analysts advised clients to buy Oracle’s five-year CDS as a hedge against AI boom risks. Morgan Stanley’s models point to further spread widening, potentially toward 150 basis points if uncertainty over Oracle’s financing plans persists.

That’s not about a single quarter. That’s about whether the infrastructure buildout is being financed at a price that makes sense if the revenue line comes in later than planned.

Then you have the next layer of financial creativity.

Companies like Lambda and CoreWeave have issued debt collateralized by high-end GPUs. Asset-backed securitization is entering infrastructure finance. This is how you expand funding capacity when conventional balance sheets start to feel tight.

Financial innovation doesn’t automatically mean “bubble.” It means incentives are pushing capital to stretch. Sometimes that’s healthy. Sometimes it’s how you hide risk inside a wrapper until it becomes someone else’s problem.

J.P. Morgan Private Bank analysis notes that nearly 40 percent of the S&P 500’s market capitalization feels direct impact from AI-related perceptions or realities. That’s a lot of market cap leaning on a single narrative.

And yes, people always reach for bubble analogies.

Railroads built too much track. The 90s built too much fiber. By mid-2001, only 10 percent of installed fiber was lit, and each lit fiber used just 10 percent of available wavelengths.

Here’s what’s different today, at least on the surface.

Data center vacancy rates are at record lows of 1.6 percent. Three-quarters of capacity under construction is pre-leased. Components across the computing, power equipment, and data center value chain are scarce relative to demand. Latest earnings confirmed AI use is driving real revenue growth for the largest companies.

So it’s not obviously “empty capacity.” Not yet.

J.P. Morgan’s framing is interesting. “The risk that a bubble will form in the future is greater than the risk that we may be at the height of one right now.”

That reads like a bank trying to be careful. But I get what they mean. This cycle can still run for a while because the near-term utilization looks real. The danger is what happens when financing costs rise and performance becomes less differentiated.

The Federal Reserve cut rates to 4.25 to 4.50 percent in December 2025. That supports credit. But the committee projects only one or two additional cuts for all of 2026. So conditions aren’t going to keep easing. They’re going to normalize.

And in a normalizing rate world, infrastructure financing gets pickier.

Morgan Stanley estimates that from 2025 to 2028, about $800 billion of private credit capital will be required to finance AI data centers, renewable power, and fiber networks. Around one-third of the $2.9 trillion total capital expenditure expected across those categories. Insurance companies, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds are becoming the natural buyers through structured vehicles.

If these projects don’t generate the returns the spreadsheets promised, the exposure isn’t sitting with tourists. It’s sitting with institutions that don’t like surprises.

The application layer opportunity the market keeps underweighting

Here’s where I think the framing gets lazy.

People talk about “AI” like it’s one trade. It’s not. There’s a real split between the parts of the stack that are becoming interchangeable and the parts that sell measurable outcomes.

While infrastructure players wear elevated credit risk, downstream software companies selling enterprise AI platforms are seeing real revenue acceleration.

Palantir exceeded $1 billion in quarterly revenue for the first time in Q2 2025, driven by 48 percent year-over-year growth. That’s a real inflection from 12.7 percent growth in Q2 2023.

The part that matters most isn’t the headline quarter. It’s the pattern. Q2 marked the eighth consecutive quarter of accelerating revenue growth. That acceleration is being driven by enterprise adoption of Palantir’s AI Platform, which acts like an AI operating system for customers. The company’s Q3 revenue guide projected 49.5 percent year-over-year growth, the highest sequential growth guide in company history.

That’s what an application layer pull looks like when it’s real.

Infrastructure is competing on cost of capital and cost per token. That’s a rough business if pricing compresses and financing tightens at the same time.

Applications that solve specific business problems are different. They’re selling “you save money” or “you make money” or “you avoid risk.” That is where pricing power lives if AI actually delivers productivity.

I keep coming back to one simple split.

Companies that create value using AI will do better than companies that build AI, if the model layer gets cheaper.

The market has not fully priced that divergence. Investors are still crowded into infrastructure plays and model builders.

Salesforce and Snowflake are examples of downstream enterprise service companies where the business model can work if customers see real net worth improvements. That doesn’t mean valuations are always right. It means the value proposition is easier to defend than “I have a slightly better chatbot.”

Then you get this seemingly unrelated datapoint that I think matters more than it looks like it should.

Dollar Tree and Dollar General outperformed the Magnificent Seven technology stocks significantly in 2025. Shares surged about 57 percent and 64 percent year-to-date. That beat Nvidia’s 34.2 percent return and beat the Roundhill Magnificent Seven ETF’s 23.7 percent return.

That’s not a meme. It’s consumer behavior.

Dollar General reported same-store sales up 2.5 percent in Q3. Dollar Tree’s same-store sales jumped 4.2 percent. Dollar Tree added 3 million new shoppers to its customer base of 100 million. About 60 percent of Dollar Tree’s new shoppers earn over $100,000 annually.

Wealthier consumers are trading down.

That’s a friction signal. It suggests the underlying economy is tighter than the headline aggregates make it feel. And it matters for AI because AI spending, especially at the application layer, ultimately depends on budgets.

If purchasing power weakens, companies squeeze discretionary spend. If budgets tighten, software expansions slow. If software expansions slow, infrastructure utilization assumptions start to wobble.

The loop connects.

What China’s technology lead actually means for this cycle

I think people reach for “China leads in tech” as a generic fear headline. That’s not how I read it.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s Critical Technology Tracker is one of the cleaner ways to quantify where the research frontier is actually moving.

The 2025 update expanded the finding. China now leads in 90 percent of the world’s strategic technologies out of 44 identified. China controls the majority with 37 technologies where it’s the clear leader and 10 where it has a virtual monopoly.

In eight of the ten newly added technologies in 2025, China has a clear lead in global share of high-impact research output. Four technologies, cloud and edge computing, computer vision, generative AI, and grid integration technologies, carry high technology monopoly risk. That’s concentration of expertise inside Chinese institutions.

When you look at the top 10 percent of high-quality publications, China surpasses the United States across all eight critical technology domains measured. The gap is especially wide in energy and environment. China accounts for 46 percent of top-tier publications versus 10 percent for the US.

Then you layer on the structure.

China explicitly integrates academia, industry, and military through Military-Civil Fusion. It removes barriers between civilian and military sectors and speeds development of emerging technologies. China’s STEM emphasis has it awarding more STEM degrees than any other country, more than four times the number awarded in the US.

That compounding talent pool is a structural advantage. It doesn’t get neutralized by building more data centers in Louisiana.

And the open-source strategy amplifies it.

While US companies pour capital into proprietary infrastructure that can get economically stale if the model layer commoditizes, Chinese and European firms are pushing releases that maximize adoption speed.

DeepSeek’s $294,000 training cost is a punchline, but it’s also a warning. Efficiency wins compound too.

One more uncomfortable point.

US export controls on advanced semiconductors slowed Chinese access to the frontier. They did not stop Chinese firms from producing models that appear near state-of-the-art. The H800 chips used to train DeepSeek became forbidden from sale to China in 2023. Chinese engineers worked inside the box and still shipped something that forced the West to pay attention.

So export controls may buy time. They don’t guarantee outcome.

If the response is “duplicate the same proprietary models with even more capital,” that starts to feel like fighting the last war with bigger checks.

The indicators I’m actually watching

I can see seven numbers that matter more than most of the debate. Not because they predict anything with certainty, but because they tell you when the story is bending.

First, OpenAI’s subscriber base and revenue per user. HSBC’s projection of negative cumulative free cash flow through 2030 depends on specific revenue assumptions. If revenue growth decelerates below 40 percent annually, the funding shortfall accelerates. Subscriber counts and average revenue per user are early-warning signals.

Second, the pace of open-source releases that are genuinely competitive in enterprise tasks. Benchmark scores are noisy, but the direction is obvious. If Meta, Mistral, and DeepSeek keep landing “good enough” models for common enterprise workloads, subscription pricing power gets squeezed.

Third, whether Oracle’s credit stress spreads to other infrastructure-heavy names. Oracle’s CDS is one canary. If you see stress show up in other places funding data centers, that’s the market saying the financing stack is getting tight.

Fourth, language shifts on hyperscaler earnings calls. I’m not looking for a capex cut headline. I’m looking for subtle changes in how they talk about sustainability, paybacks, and pace. When executives stop sounding casual about infinite scaling, the cycle has turned.

Fifth, Federal Reserve communication around 2026 rate expectations. The committee projects limited cuts. If inflation forces even a hint of future hikes, financing costs tighten right when funding needs peak. That’s when marginal projects start slipping.

Sixth, private credit spreads on AI infrastructure. Meta’s Hyperion financing priced at 225 basis points over Treasuries. If subsequent deals clear at materially wider spreads, that’s investors demanding more compensation for return uncertainty. Morgan Stanley’s estimate of $800 billion needed through 2028 doesn’t work if spreads blow out.

Seventh, data center vacancy rates and pre-leasing. Today’s numbers, 1.6 percent vacancy and three-quarters pre-leased, say demand is real. If vacancy rises above 3 percent or pre-leasing drops below 60 percent, it’s the first sign that capacity is starting to outrun actual utilization.

The bifurcation I think people are missing

I don’t think the most likely outcome is “everything is fine” or “everything collapses.”

I think the most likely outcome is a split.

Proprietary models probably keep premium pricing in high-value work with strict requirements, compliance, support, and indemnification. Enterprise customers paying for GPT-4.1 or Gemini 2.5 Pro aren’t only paying for performance. They’re paying for reliability, documentation, legal cover, and someone to call when it breaks.

That can last a long time.

Open source captures the broad middle. Routine enterprise tasks. Internal copilots. Customer service layers. Summarization. Basic analytics. Most consumer use. DeepSeek, Mistral, and Llama variants are already good enough for a huge share of workloads at much lower cost.

So commoditization hits the fat middle first, not the premium tier.

Data centers likely stay highly utilized through 2027 and 2028 based on current commitments. The pre-leasing and vacancy rates support that. The stress shows up first in returns, not in empty buildings.

Infrastructure returns can come in below plan while the facilities are still “full.”

That’s what breaks levered underwriting. It doesn’t take a collapse. It takes disappointment.

And the real vulnerability is still the dependency chain.

If AI applications don’t deliver productivity improvements that show up in financial statements, return on data center infrastructure declines. If returns disappoint, debt service gets tighter. If debt stress shows up, lenders and structured vehicles have to reprice collateral. If financing tightens, new projects don’t get built. If new projects don’t get built, the growth assumptions embedded across semiconductors, data centers, and software get revised down together.

One loop feeds the next.

The opportunity, to me, is still downstream. It’s in the application layer. It’s in companies that can point to value created, not models built.

Palantir’s acceleration is one example of that dynamic. The market is still crowded into infrastructure and model narratives. The rotation into “value capture” hasn’t fully happened.

And China’s lead across critical domains is not a market timing tool. It’s a structural fact with consequences. The open-source strategy amplifies that structural fact. If US companies keep concentrating capital into proprietary infrastructure while competitors accelerate adoption through open source, the US may win the buildout and lose the pricing.

That’s a weird way to lose, but it happens all the time.

The $1.4 trillion question is whether OpenAI and similar companies can generate enough revenue to justify infrastructure spending that currently exceeds revenue by about 100 times. HSBC’s work suggests not by 2030. Credit markets are starting to price that possibility through Oracle’s spreads and the amount of financial engineering required to keep data center debt from sitting in plain sight.

AI is real. Productivity gains will be real.

But the financial underpinnings are not as clean as the headlines make them feel.

I’m watching three things.

OpenAI revenue traction. Open-source parity. Private credit spreads.

That’s where this story turns first.